Hall of Fame

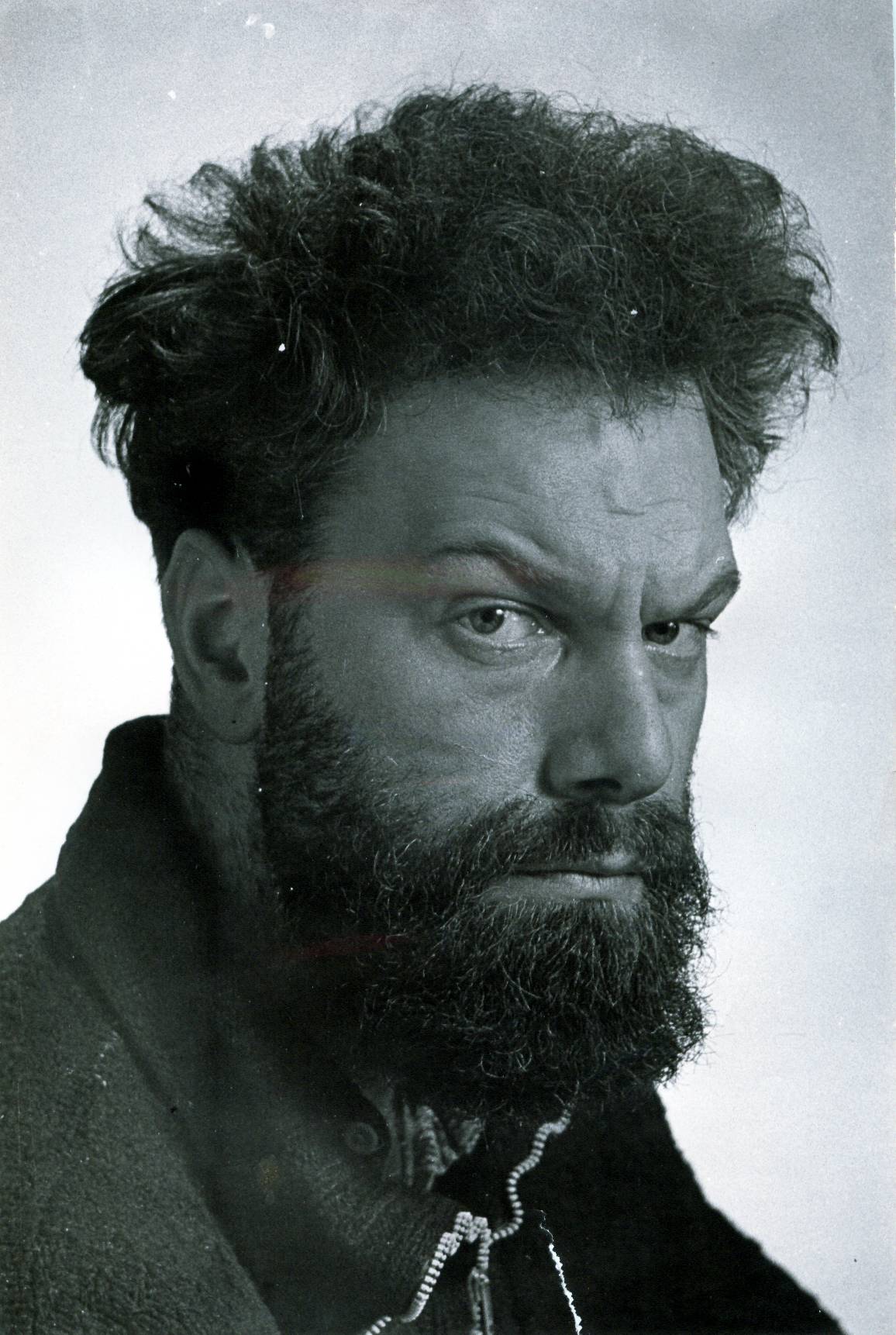

Otakar Diblík

Otakar Diblík

19 August 1929, Brno – 12 February 1999, Praha)

In 1948, it seemed that Otakar Diblík's life and creative career were clearly traced. The son of a Brno builder (born on 19 August 1929) was admitted to study at the Faculty of Architecture and Civil Engineering at the University of Technology of Dr Edvard Beneš.

Early on, Diblík was strongly influenced by one of his teachers, who somewhat "diverted" the creative path Diblík was expected to take. It was not Professor Bohuslav Fuchs, the author of the famous Avion Hotel and other exceptional functionalist buildings, nor any of the famous architects, who taught at the school, but the sculptor Vincenc Makovský, who headed the Institute of Drawing and Modelling at the Brno University of Technology. Makovský also passed on to his students his experience from his time at the School of Art in Zlín, where he designed the shapes of machine tools and tools during the Protectorate and inspired Zdeněk Kovář and other students to dedicate themselves to what is today called industrial design. Makovský and Diblík, who was technically talented and handy, became close colleagues and good friends. Otakar Diblík graduated from the school with two diploma theses - the second one was a project of a mobile radiogram.

In the meantime, the Communists seized control of Czechoslovakia for good. The Brno University of Technology saw the name of the "bourgeois" president in its name removed, and the origin of Otakar Diblík was now politically undesirable, too. Instead of basic military service in the Auxiliary Technical Batallion, he went to work for three years at the Military Project Institute (VPÚ). It was during this time that, by an unlikely coincidence, he got the opportunity to work in the automotive industry. He worked as an in-house designer, the first such position in Czechoslovakia.

In 1956-1959 he participated in the development of the product portfolio of Karosa, a bus manufacturer in Vysoké Mýto. The success of the exclusive interior of the special edition of the Š 706 RTO bus for the EXPO ´58 World Exhibition in Brussels brought Diblík to the Tatra design office in Prague. Tatra collaborated on the development of the shape design of the new electric locomotive of the Pilsen Škoda (V. I. Lenin Works back then) and Diblík was assigned to design the locomotive head and casing. His design received such support from the company management that the best fitting production technology was chosen with regard to the shape design, and not the other way around as was usually the case. The decision was made: Škoda would launch the production of the world's first laminate locomotive.

The laminate locomotive design eased Diblík’s way to the Union of Czechoslovak Visual Artists, i.e. to receive the status of a “freelance industrial artist”. He collaborated with several design development and production companies, including ČKD in Prague, Tatra plant in Bratislava, Zetor in Brno and Adamovské strojírny. He also designed handles and fittings for the Janáček Theatre in Brno. The total number of commissions was not huge, but it had an extraordinary proportion of remarkable and exceptional projects. They often set the direction of the design solution for a specific type of product for the next few decades, such as the famous agriculture tractor Zetor Crystal. The tractor instantly draws attention to its angular shape, generously glazed cabin and headlights set into the bonnet. It is thus easy to miss the slightly offset bonnet, which allows the use of a straight, continuous windscreen.

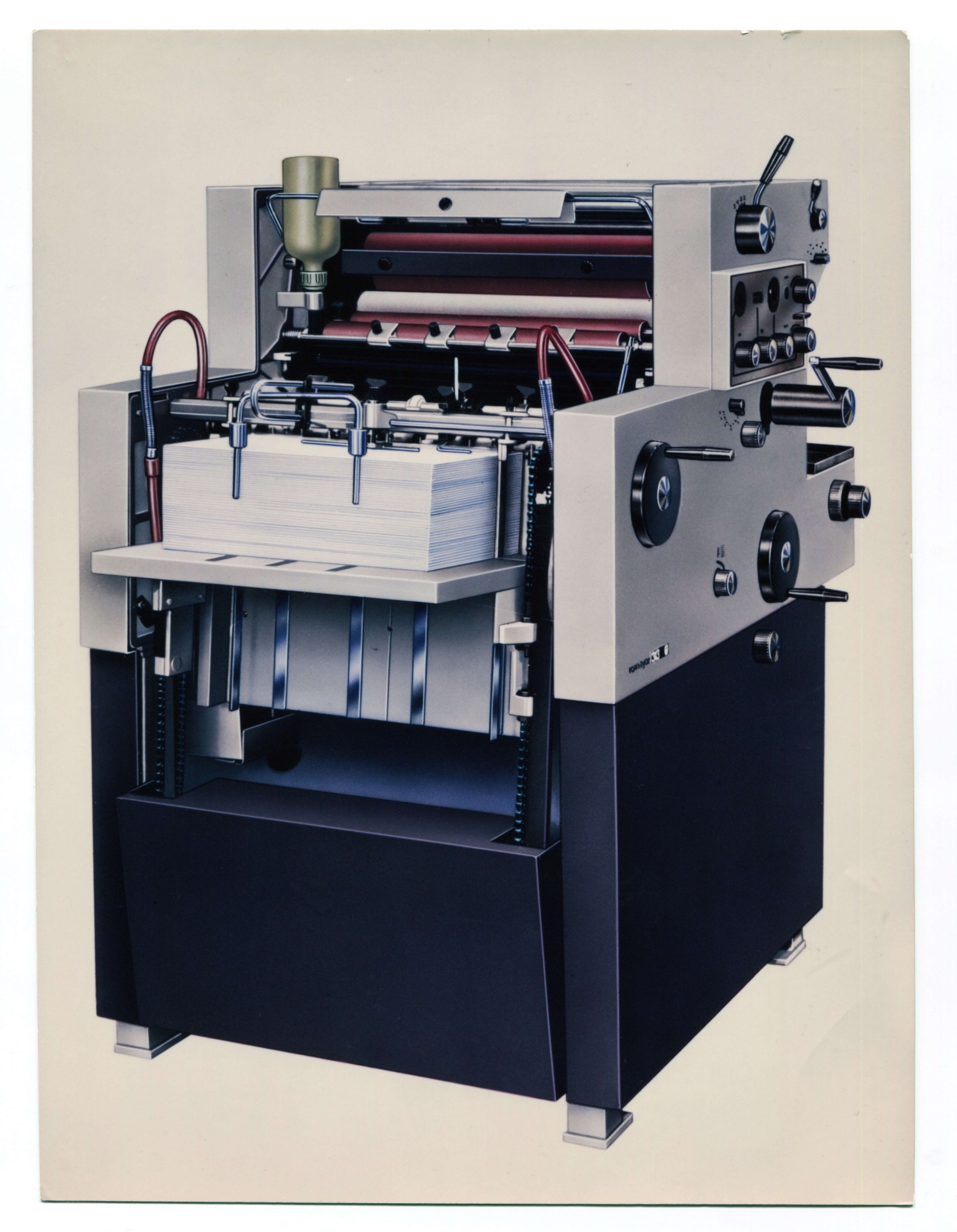

During the development of the Dominant and Romayor printing presses for Adamovské strojírny, Diblík surprised people with his deep interest in the opinions of printers, printing technology and the details of the operation of the presses, as well as his open and friendly approach to his co-workers. Diblík’s consistency can be illustrated by a story typical of him: before submitting his intended colour scheme, he had his new Hillman Minx car fitted with the two-colour combination. After some time, when he tested the colour combination and found it suitable, he submitted it to the design management.

Diblík was also extremely hardworking. He could "go" without a break for two weeks until the project was successfully completed. Once that was done, he left with a travel bag over his shoulder and did not show up for several weeks.

But the most adventurous years were yet to begin for Diblík, who was almost 40 by then. On 22 August 1968 he emigrated to Austria via Yugoslavia. From the refugee camp, he wrote to the Milanese designer Rodolfo Bonetto, whom he had met a few years earlier. In 1969, he became a designer and then in the early 1980s a chief designer of Bonetto's renowned studio with a considerable scope. Here, in a hectic pace, designs were created for machine tools, consumer electronics, household appliances, computer and medical technology, and dashboards for cars, furniture, and sporting goods. Otakar Diblík created about 270 projects at Bonetto, the vast majority of which were brought to production. Many of them carry Diblík's original style, characterized by a solid construction of the shape "from the inside" combined with originality and humility to the purpose for which the object is intended.

After the Velvet Revolution, Otakar Diblík headed the product design studio at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. He travelled between Milan and Prague, dedicated himself to his great hobby - astronomy and building telescopes – and designed a new generation of printing machines for Dobrušské strojírny, with whose designers he had successfully worked twenty-five years earlier.

Professor Otakar Diblík died suddenly of a heart attack in his school studio on 12 February 1999.

Diblík’s extraordinary design work and interesting life story were first introduced to the public in an interview with curator Jana Johanna Pauly, the founder of the industrial design collection. The interview was published shortly after Diblík's sudden death in 1999 in the Design Centre Bulletin of Czech Republic. Five years later, to mark Diblík's 75th birthday, the first retrospective of his work was opened in collaboration with the National Technical Museum and the Academy of Fine Arts. A series of reruns followed, the first and most notable of them being a collaboration with the Faculty of Architecture of the Brno University of Technology - Otakar Diblík's alma mater.

General Čepička offered us military service at the Military Design Institute in Prague, which was quite good, because we were otherwise assigned to the Auxiliary Technical Battalion. Unfortunately, the military service was extended to 28 months due to the political situation caused by the Korean War. And imagine that one day, when I was hitchhiking home from the army to Brno in a terrible drizzle, a Tatra 603 stopped for me in Jihlava on the square and gave me a ride. All the way there I explained to him my views on car design in a dynamic and verbose manner. And he said to me: "Hey soldier, when you get out of the army, come to me at the Ministry of Automotive Industry and I will give you some recommendations". So I went there and asked for Zatloukal. They said, "Yeah, Comrade Minister Zatloukal has an office over there." So the minister gave me four recommendations, for the Karosa, the Tatra, the Škoda and the Liaz. That was in 1961.

First, I went to Karosa in Vysoké Mýto. They were all of them Sodomka’s guys there, and they said, "We don't need an artist, we do it ourselves." So I told them, well, I have a letter for Liaz too. And they said, "No, no, no, man, stay here!"

I left Bonetto's studio in 1989. Then, by coincidence, Bořek Šípek approached me in Milan, he was already working in Prague. He invited me to audition for a position in the Design Studio at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. I thought I'd give it a try because suddenly I had the desire to go back to Prague.

So here I am, trying to educate a new generation of designers. It's not easy with them, but I love teaching them. The design studio here has become my second home. I want to pass on some of my years of experience and teach them a holistic view of industrial design.

Excerpts from the interview of Otakar Diblík and Jana Johanna Pauly, 3. 2. 1999