Hall of Fame

Bořek Šípek

In 1995, an exhibition catalogue for the Museum of Applied Arts in Frankfurt written by Volker Albus and Volker Fischer was published, entitled 13 After Memphis. The book assembled a generation of designers influenced by Memphis, but who were in no way connected to the movement. The 13 designers ranged alphabetically from Ron Arad, Bořek Šípek to ZEUS, and geographically from the UK to Italy. Some of the designers have now fallen into obscurity, known to collectors only; some of the groups don't exist anymore, while others have become very famous. Leafing through the book today, the reader is transported back to a special moment in design history. It's fascinating to see how different languages can remain completely independent of nationality and yet still (!) impart information about the different countries and cultural mind-sets.

The early nineties was an exciting era and not just for me. I had just graduated and started working as an assistant at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna with Deyan Sudjic, who opened my eyes to design in a different way. I had just switched from design practice to theory, marking a personal moment at which I started looking at design from a different perspective. Suddenly I wasn't a maker anymore, but an observer; something I've never stopped doing since. My fascination with Memphis had just started to fade at that time. We made a number of wonderful field trips with our students. One led us to the Netherlands where I met Bořek Šípek for the first time. I still don't know why he was living in the Netherlands back then. He had studied at the High School of Applied Arts in Prague, left Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic and Slovakia) in 1968, moved to Hamburg to study architecture, studied philosophy in Stuttgart and then got his PhD in architecture in Delft. This may be the reason why he did not go back to Czechoslovakia. Or maybe the Netherlands offered just the right measure of freedom or that relaxed vibe he needed, which is very much in keeping with what he always was and still is – a special personality with a melancholic touch, a philosophical attitude and a deep love and understanding of handicraft.

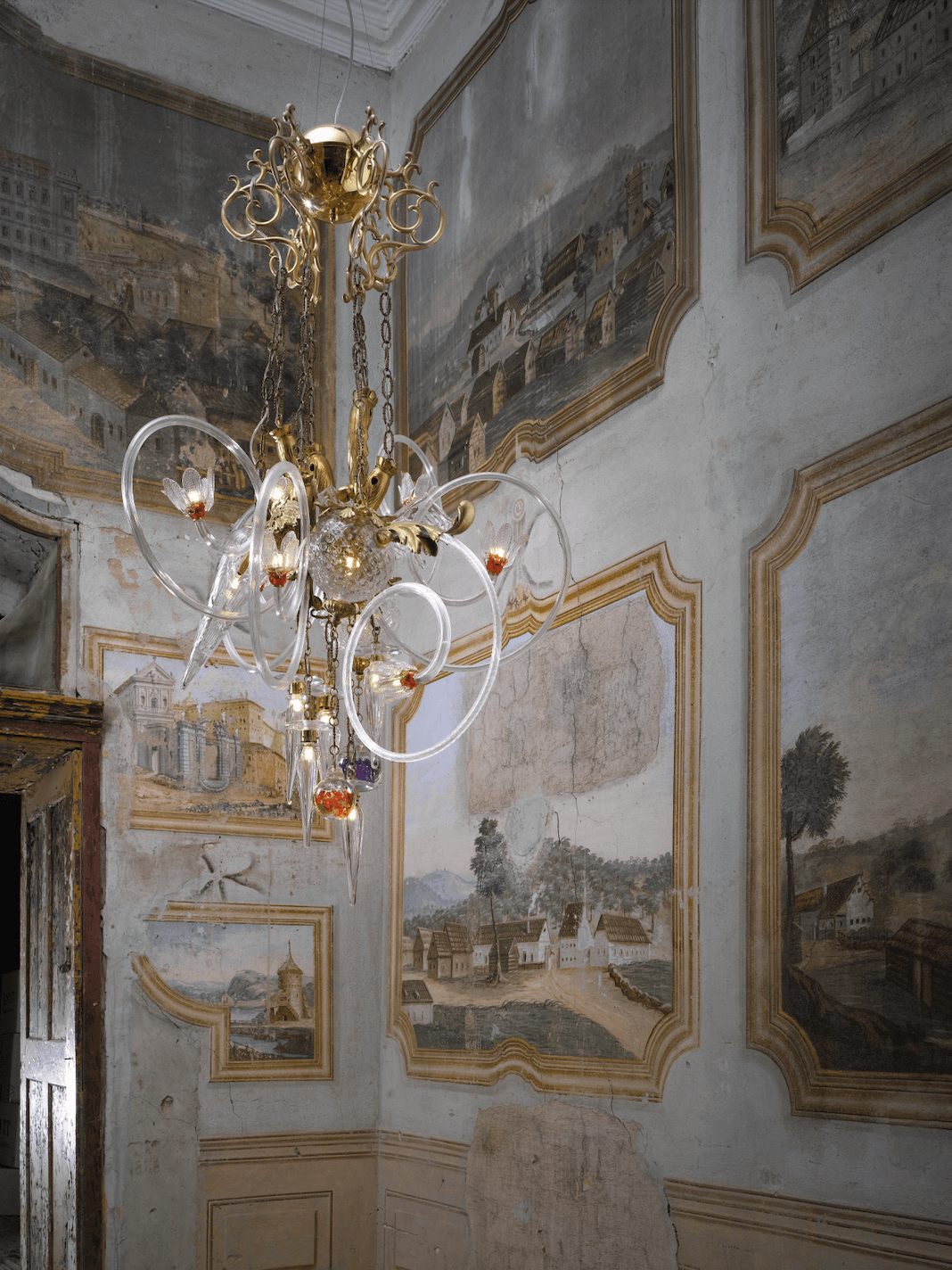

Šípek was very successful at that time. Even though he was working for prominent companies including Driade, Vitra and Wittmann, he hadn't lost his connection with the artisan world of Czech glass. Serial production and his love of handicraft coexisted side by side during that intense design period of the nineties. The pieces designed by Šípek speak a very special language which translates Czech poetry and a faiblesse for fairy tales and forests into objects. One can also detect a certain morphing of Czech cubism into a post-modern expression. For this reason, the pieces may seem out-dated today but I am convinced that his designs are deep-rooted in the tradition of Czech design history and that they add an essential, priceless value to international design – especially now that the Czech Republic's design scene seems to have rediscovered the value of handicraft and its own tradition of master glassmakers. In that context, one suddenly understands Šípek's vision and his role as an ambassador even though he was a refugee at that time.

Later, he was invited by Vaclav Havel to design for Prague Castle, paving the way for these two exceptional men to combine their vision of a new Czech country. Šípek was the first architect to design for the castle after Josip Plečnik. Becoming a professor at the AAAD in 1990 allowed him to take part in rebuilding the Czech design scene. When he was appointed as a professor at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna, I got the chance to meet him again and soon became acquainted with another quality to his personality. In the years he taught in Vienna, following Ron Arad, he had a great influence on a number of Austrian designers. His generosity in allowing students to develop their qualities and his sincere interest in discussion – very often of a philosophical nature – are truly exceptional. He has never imposed his own signature design style; rather he prefers to engage in discussions that are anything but easy, since we all know that design is a field that comes with big responsibilities. That is probably one of his greatest virtues: as well as being a great designer, he is incredibly humble – fully invested in others (no matter who they are) and in sharing his vision and knowledge.

Tulga Beyerle